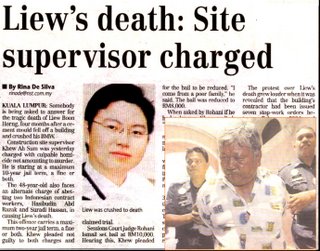

In my recent article Construction Site Supervisors are held liable for negligence? Khew Ah San, the sub-contractor supervisor for the Plaza Damas project, was charged in the court with manslaughter and abetment in causing the death of Dr Liew Boon Horng through negligence. I posed the question:

What about vicarious liability?

What about Occupiers Liability?

Some of my friends and readers asked me to explain.

Occupiers Liability law relates to such liability as regard to visitors and trespassers of property. It refers to the fact that an owner of a property will owe a duty of care to the person who come on the premise and this duty is basically to ensure that people are not harmed by the state of the premise or activity carried on to the premises (see: Fairchild v Glenhoven Funeral Services (2002)).

In United Kingdom, the law relating to such liability is largely to be found in the Occupiers Liability Act 1957 (for visitors) and the Occupiers Liability Act 1984 (as regard to non-visitors).

The Occupiers Liability Act 1957 sets out the duty of care to be imposed upon an occupier in respect of lawful visitors. By virtue of the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957, the occupier of premises owes the same common duty of cure to lawful visitors to or on his premises. Note that the liability to compensate persons injured on premises owing to their dangerous state is in general upon the occupier and not the owner. The criterion for determining occupation is effective or sufficient degree of control. Thus one does not need to be in actual possession of the premises in question in order to be in occupation or to be deemed an occupier. It is sufficient if he/she has a substantial degree of control of the premises in question. He owes this duty of care to all lawful visitors to the premises except in so far as the duty is modified by agreement.

Under the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984, a statutory duty is also owed by the occupier to persons other than his visitors – e.g. to trespassers. A trespasser is a person who intentionally goes on to land in the possession of another without lawful authority. Thus, for instance, members of the public who are admitted to a theatre are visitors to whom the occupier of the premises owes, prima facie, the common duty of care. They are visitors in the sense that a theatre ticket is a license coupled with an agreement not to revoke that licence until the termination of the performance. See the case of Hurst v Picture Theatres Ltd (1915) 1 KB 1 CA.

The question may be asked as to who is a visitor? At common law generally speaking, it was necessary to distinguish between invitees, licencees and trespassers on premises. The approximate distinction between invitees and licencees was that an invitee was requested to enter the premises in the interest of the occupier, where as a licencee was merely permitted to enter. But this does not seem too important any longer owing to the fact that "visitor: for the purposes of the occupiers Liability Act 1957 embraces those persons who are invitees or licencees at common law. See The Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957, Section 1 (2). This in essence includes anyone to whom the occupier gives any invitation or permission to enter or use the premises. In order to have a clearer understanding of this area of tort jurisprudence, it is still important to strike a distinction between those persons who are and those who are not visitors, since the former, (i.e. those who are visitors) are governed by the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 and those who are not visitors are governed by the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984. The two legislations/Acts were enacted to have effect in place of the rules of common law. Note, however, that the common law imposed on the occupier a higher duty of care towards invitees than towards licencees. The Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 determines whether any duty is owed by a person as occupier of premises to persons other than his visitors, in respect of any risk of their suffering injury on the premises by reason of any danger due to the state of the premises or to things done or omitted to be done on them and if so, what the duty is.

Under the common law, the occupier owed a "humanitarian duty" to the trespasser. See the exemplification of this principle in the case of British Railways Board v Herrington (1972) AC 877 where the defendants owned an electrified line which was fenced off from a meadow where children lawfully played were held liable when some children got injured on the premises. In 1965 the fence had been in a dilapidated condition there for several months and through it people took a short cut across the line. The defendant’s stationmaster, who was responsible for that stretch of line, was notified in April 1965 that children had been on it, but the fence was not repaired. On June 7,1965, the Plaintiff, then aged six, trespassed over the broken fence from the meadow where he had been playing and was injured on the live rail. He brought an action claiming damages for negligence, and the judge held that the defendants were negligent in allowing the fence to fall and remain in a state of disrepair and were liable to the Plaintiff since the emergence of a child trespasser from the meadow on to the line was reasonably foreseeable [In tort jurisprudence the defendant is always liable for the damage or injury that he or a reasonable person can foresee and may not be liable for damage or injury which he or any reasonable person could not have foreseen .

Another case of importance is the decision of the Privy Council in the case of Overseas [U K ] Tankship Ltd v Morts Dock Engineering Co Ltd[The Wagon Mound] 1961, per Viscount Simonds.] The Court of Appeal in the case of British Railway Board v Herrington as mentioned earlier on, further held that the defendant acted in reckless disregard of the Plaintiffs safety. On further appeal to the House of Lords, it was held that the Defendants were in breach of their duty to the Plaintiff who was entitled to damages.

The Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 was passed following a recommendation of the Law Commission that the duty expressed in varying terms by the House of Lords in the Herrington case.

Section 1 of the 1984 Act provides that it is to replace the common law rules concerning liability for personal injury to trespassers and other entrants outside the protection of the 1957 Act. Thus, a trespasser can bring an action for personal injury against occupier of premises in certain circumstances under the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984. This does not include claims for property damage.

Section 1, sub-section 4 of the Occupiers Liability Act 1984 imposes on the occupier of premises a duty to take "such care as is reasonable in all the circumstances of the case" to see that the trespasser does not suffer injury on the premises" by reason of any danger on them, provided three conditions are met. These are (a) that the occupier knows, or ought to know, of the existence of the danger on his premises and (b) that he knows or ought to know that the trespasser is in the vicinity of the danger, or likely to come into it, and (c) that the risk is one against which in all the circumstances of the case, he may reasonably be expected to offer some protection. In essence we owe a duty of care to a thief or burglar who might sneak on to our premises to steal or rob under the Occupiers Liability Act 1984.

There is no law in Malaysia which is equivalent to the United Kingdom Occupiers' Liability Act, 1957. In such a situation, common law principles in United Kingdom will apply to Malaysian law (see: Section 3(2) Civil Law Act 1956).

If that is the case then the next question to ask is who is the occupier for Plaza Damas Project? Is it the developer, the property owner, the contractor, the sub-contractor or local authority or are all are jointly liable in their respective capacities?

This, I will have to leave it to the court to decide.

The next question to be asked is: "What about the law of negligence"?

The issue in this case is to establish the negligent act which resulted in the kind of damage that in fact occurred. It is also necessary to consider whether an action for vicarious liability (which means employer will be liable for employees negligent act) could be established in regard to the breach of a duty of care.

In order to hold an employer vicariously liable for the tort committed by the employee, the plaintiff must establish three elements: (1) that the employee (tortfessor) is under the employment of the defendant company; (2) that the employee had committed a tort; (3) and the employee had committed the tort during the course of employment. However, an employer is only liable for the tort of his own employees; not those of the independent contractors. So, for vicarious liability, it is necessary to distinguish between an employee and an independent contractor.

In Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd v Minister of Pensions & National Insurance (1968), it was held that there were 3 conditions for the existence of a contract of service. (1) The employee agrees to provide his work and skill in return for wages or other renumeration; (2) The employee agrees, expressly or impliedly to be directed as to the mode of performance; and (3) The other provisions of the contract are consistent with its being a contract of service.

In this case, Khew Ah Sum is employed by San Meng Construction, the sub-contractor, who then is employed by the main contractor and property developer. Who then should be held liable?

In Mersey Docks & Harbour Board v Coggins & Griffith Ltd (1967) the court held that the burden of proof rests upon the general or permanent employer to shift the prima facie responsibility to the hirer (in this case, the main contractor or property developer).

The important question is: "Who is entitled to give the orders as to how to do the work and how it should be done." The ultimate criteria is: "Who is in control over the method of performing the work?"

In the case of Plaza Damas, it seems that the sub-contractor, San Meng Construction holds the controlling power and influence over the methods of construction, and not Khew Ah Sum. At such, it is submitted that Khew could rely on this defence and be acquitted over the charge of manslaughter.

How is it that the prosecution had decided to indict Khew instead of San Meng Construction? It is a fact that the prosecution would be able to prove beyond reasonable doubt that San Meng Construction had breach the duty of care and will be liable. That way, justice would be seen to be done.

It seems that prosecutions will lose this cases ...

and the reasons ... lack of legal knowledge.

This is just my layman's opinion - that Khew need not fear. There are sufficient legal authorities to defend him. The prosecution may have to go back to law school. I can be wrong; this is just a legal discussion and not intended to form a subjudice. If it is of the opinion that it could constitute subjudice, then I will delete this post.

I believe the DPP would amend the charge for manslaughter Section 304(b) of the Penal Code or the alternative charge under Section 109 of the Penal Code to charges under section 24 Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994.

In Section 24 OSHA 1994,the general duties of employees at work are:

(1) It shall be the duty of every employee while at work

(a) to take reasonable care for the safety and health of himself and of other persons who may be affected by his acts or omissions at work;

(b) to co-operate with his employer or any other person in the discharge of any duty or requirement imposed on the employer or that other person by this Act or any regulation made thereunder;

(c) to wear or use at all times any protective equipment or clothing provided by the employer for the purpose of preventing risks to his safety and health; and

(d) to comply with any instruction or measure on occupational safety and health instituted by his employer or any other person by or under this Act or any regulation made thereunder.

(2) A person who contravenes the provisions of this section shall be guilty of an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to a fine not exceeding one thousand ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months or to both.

Under Section 51 OSHA 1994, the liability for offences upon conviction which is expressly provided for, under under section 24(2) will be upheld.

The charges under Penal Code is between 2-10 years jail term or a fine, or both.

The charge under OSHA is a fine not exceeding RM1,000 or a jail term not exceeding 3 months or both.

It's much lighter sentence and by the time the judgment is pronounced, Khew would have been considered to have served his term and be a free man.

What about vicarious liability?

What about Occupiers Liability?

Some of my friends and readers asked me to explain.

Occupiers Liability law relates to such liability as regard to visitors and trespassers of property. It refers to the fact that an owner of a property will owe a duty of care to the person who come on the premise and this duty is basically to ensure that people are not harmed by the state of the premise or activity carried on to the premises (see: Fairchild v Glenhoven Funeral Services (2002)).

In United Kingdom, the law relating to such liability is largely to be found in the Occupiers Liability Act 1957 (for visitors) and the Occupiers Liability Act 1984 (as regard to non-visitors).

The Occupiers Liability Act 1957 sets out the duty of care to be imposed upon an occupier in respect of lawful visitors. By virtue of the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957, the occupier of premises owes the same common duty of cure to lawful visitors to or on his premises. Note that the liability to compensate persons injured on premises owing to their dangerous state is in general upon the occupier and not the owner. The criterion for determining occupation is effective or sufficient degree of control. Thus one does not need to be in actual possession of the premises in question in order to be in occupation or to be deemed an occupier. It is sufficient if he/she has a substantial degree of control of the premises in question. He owes this duty of care to all lawful visitors to the premises except in so far as the duty is modified by agreement.

Under the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984, a statutory duty is also owed by the occupier to persons other than his visitors – e.g. to trespassers. A trespasser is a person who intentionally goes on to land in the possession of another without lawful authority. Thus, for instance, members of the public who are admitted to a theatre are visitors to whom the occupier of the premises owes, prima facie, the common duty of care. They are visitors in the sense that a theatre ticket is a license coupled with an agreement not to revoke that licence until the termination of the performance. See the case of Hurst v Picture Theatres Ltd (1915) 1 KB 1 CA.

The question may be asked as to who is a visitor? At common law generally speaking, it was necessary to distinguish between invitees, licencees and trespassers on premises. The approximate distinction between invitees and licencees was that an invitee was requested to enter the premises in the interest of the occupier, where as a licencee was merely permitted to enter. But this does not seem too important any longer owing to the fact that "visitor: for the purposes of the occupiers Liability Act 1957 embraces those persons who are invitees or licencees at common law. See The Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957, Section 1 (2). This in essence includes anyone to whom the occupier gives any invitation or permission to enter or use the premises. In order to have a clearer understanding of this area of tort jurisprudence, it is still important to strike a distinction between those persons who are and those who are not visitors, since the former, (i.e. those who are visitors) are governed by the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 and those who are not visitors are governed by the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984. The two legislations/Acts were enacted to have effect in place of the rules of common law. Note, however, that the common law imposed on the occupier a higher duty of care towards invitees than towards licencees. The Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 determines whether any duty is owed by a person as occupier of premises to persons other than his visitors, in respect of any risk of their suffering injury on the premises by reason of any danger due to the state of the premises or to things done or omitted to be done on them and if so, what the duty is.

Under the common law, the occupier owed a "humanitarian duty" to the trespasser. See the exemplification of this principle in the case of British Railways Board v Herrington (1972) AC 877 where the defendants owned an electrified line which was fenced off from a meadow where children lawfully played were held liable when some children got injured on the premises. In 1965 the fence had been in a dilapidated condition there for several months and through it people took a short cut across the line. The defendant’s stationmaster, who was responsible for that stretch of line, was notified in April 1965 that children had been on it, but the fence was not repaired. On June 7,1965, the Plaintiff, then aged six, trespassed over the broken fence from the meadow where he had been playing and was injured on the live rail. He brought an action claiming damages for negligence, and the judge held that the defendants were negligent in allowing the fence to fall and remain in a state of disrepair and were liable to the Plaintiff since the emergence of a child trespasser from the meadow on to the line was reasonably foreseeable [In tort jurisprudence the defendant is always liable for the damage or injury that he or a reasonable person can foresee and may not be liable for damage or injury which he or any reasonable person could not have foreseen .

Another case of importance is the decision of the Privy Council in the case of Overseas [U K ] Tankship Ltd v Morts Dock Engineering Co Ltd[The Wagon Mound] 1961, per Viscount Simonds.] The Court of Appeal in the case of British Railway Board v Herrington as mentioned earlier on, further held that the defendant acted in reckless disregard of the Plaintiffs safety. On further appeal to the House of Lords, it was held that the Defendants were in breach of their duty to the Plaintiff who was entitled to damages.

The Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984 was passed following a recommendation of the Law Commission that the duty expressed in varying terms by the House of Lords in the Herrington case.

Section 1 of the 1984 Act provides that it is to replace the common law rules concerning liability for personal injury to trespassers and other entrants outside the protection of the 1957 Act. Thus, a trespasser can bring an action for personal injury against occupier of premises in certain circumstances under the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1984. This does not include claims for property damage.

Section 1, sub-section 4 of the Occupiers Liability Act 1984 imposes on the occupier of premises a duty to take "such care as is reasonable in all the circumstances of the case" to see that the trespasser does not suffer injury on the premises" by reason of any danger on them, provided three conditions are met. These are (a) that the occupier knows, or ought to know, of the existence of the danger on his premises and (b) that he knows or ought to know that the trespasser is in the vicinity of the danger, or likely to come into it, and (c) that the risk is one against which in all the circumstances of the case, he may reasonably be expected to offer some protection. In essence we owe a duty of care to a thief or burglar who might sneak on to our premises to steal or rob under the Occupiers Liability Act 1984.

There is no law in Malaysia which is equivalent to the United Kingdom Occupiers' Liability Act, 1957. In such a situation, common law principles in United Kingdom will apply to Malaysian law (see: Section 3(2) Civil Law Act 1956).

If that is the case then the next question to ask is who is the occupier for Plaza Damas Project? Is it the developer, the property owner, the contractor, the sub-contractor or local authority or are all are jointly liable in their respective capacities?

This, I will have to leave it to the court to decide.

The next question to be asked is: "What about the law of negligence"?

The issue in this case is to establish the negligent act which resulted in the kind of damage that in fact occurred. It is also necessary to consider whether an action for vicarious liability (which means employer will be liable for employees negligent act) could be established in regard to the breach of a duty of care.

In order to hold an employer vicariously liable for the tort committed by the employee, the plaintiff must establish three elements: (1) that the employee (tortfessor) is under the employment of the defendant company; (2) that the employee had committed a tort; (3) and the employee had committed the tort during the course of employment. However, an employer is only liable for the tort of his own employees; not those of the independent contractors. So, for vicarious liability, it is necessary to distinguish between an employee and an independent contractor.

In Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd v Minister of Pensions & National Insurance (1968), it was held that there were 3 conditions for the existence of a contract of service. (1) The employee agrees to provide his work and skill in return for wages or other renumeration; (2) The employee agrees, expressly or impliedly to be directed as to the mode of performance; and (3) The other provisions of the contract are consistent with its being a contract of service.

In this case, Khew Ah Sum is employed by San Meng Construction, the sub-contractor, who then is employed by the main contractor and property developer. Who then should be held liable?

In Mersey Docks & Harbour Board v Coggins & Griffith Ltd (1967) the court held that the burden of proof rests upon the general or permanent employer to shift the prima facie responsibility to the hirer (in this case, the main contractor or property developer).

The important question is: "Who is entitled to give the orders as to how to do the work and how it should be done." The ultimate criteria is: "Who is in control over the method of performing the work?"

In the case of Plaza Damas, it seems that the sub-contractor, San Meng Construction holds the controlling power and influence over the methods of construction, and not Khew Ah Sum. At such, it is submitted that Khew could rely on this defence and be acquitted over the charge of manslaughter.

How is it that the prosecution had decided to indict Khew instead of San Meng Construction? It is a fact that the prosecution would be able to prove beyond reasonable doubt that San Meng Construction had breach the duty of care and will be liable. That way, justice would be seen to be done.

It seems that prosecutions will lose this cases ...

and the reasons ... lack of legal knowledge.

This is just my layman's opinion - that Khew need not fear. There are sufficient legal authorities to defend him. The prosecution may have to go back to law school. I can be wrong; this is just a legal discussion and not intended to form a subjudice. If it is of the opinion that it could constitute subjudice, then I will delete this post.

I believe the DPP would amend the charge for manslaughter Section 304(b) of the Penal Code or the alternative charge under Section 109 of the Penal Code to charges under section 24 Occupational Safety and Health Act 1994.

In Section 24 OSHA 1994,the general duties of employees at work are:

(1) It shall be the duty of every employee while at work

(a) to take reasonable care for the safety and health of himself and of other persons who may be affected by his acts or omissions at work;

(b) to co-operate with his employer or any other person in the discharge of any duty or requirement imposed on the employer or that other person by this Act or any regulation made thereunder;

(c) to wear or use at all times any protective equipment or clothing provided by the employer for the purpose of preventing risks to his safety and health; and

(d) to comply with any instruction or measure on occupational safety and health instituted by his employer or any other person by or under this Act or any regulation made thereunder.

(2) A person who contravenes the provisions of this section shall be guilty of an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to a fine not exceeding one thousand ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months or to both.

Under Section 51 OSHA 1994, the liability for offences upon conviction which is expressly provided for, under under section 24(2) will be upheld.

The charges under Penal Code is between 2-10 years jail term or a fine, or both.

The charge under OSHA is a fine not exceeding RM1,000 or a jail term not exceeding 3 months or both.

It's much lighter sentence and by the time the judgment is pronounced, Khew would have been considered to have served his term and be a free man.