You buy a house costing a million in upmarket Mount Kiara - hell of expensive, but you believe it's worth it as it's a good investment.

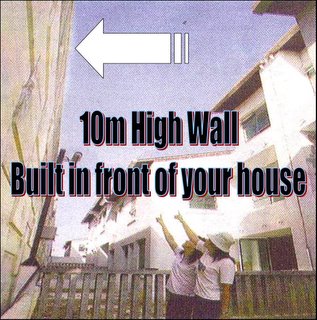

Suddenly, at the back of your house, the neighbour developer built a 10 meter high wall which blocks your rights to have good airflow and lights. Worse off, the wall develops crack and wet soil seeps out of the cracks.

Now, you are at risk that soon, you will be asked to move out of your house due to the high risk of collapse. Nobody wants to buy your house and you have hundreds of thousands in mortgage loan to settle with your bankers.

Read this story:

House owners in Villa Aseana, a new housing project in Mount Kiara are angry that a 10m high wall has been built behind their new houses.

The developer of the land next door, Merge Power S/B erected the wall so that it could fill up the land’s sloping terrain with earth for its building project.

The wall however has showed signs of cracks and soils from the other side are leaking through the cracks. The residents had written to city hall and City Hall had issued an order to the developer to tear down the wall. The approved plan only allowed a 1m high wall. City Hall said they had given the developer one month’s notice to take down the wall or sent in the amended drawings for approval. City Hall said they will continue to monitor the developer and ensure that they abide by the plan.

What will you do if you are the dominant owner? What is your rights against the servient owner?

Let's look at a few English cases:

Bernstein v Skyviews & General Ltd [1978] QB: The case establishs that a landowner does not have unqualified rights over the airspace over his land. Facts: Skyviews employee flew over Bernstein's land, took photograph of his house and offered it for sale to Bernstein. Bernstein too exception and sued for trespass. Griffith J. dicta: "I can find no support in authority for the view that a landowner's rights in the air space above his property extend to an unlimited height. The problem is to balance the rights of an owner to enjoy the use of his land against the rights of the general public to take advantage of all that science now offers in the use of air space. This balance in my judgment is to restrict the rights to such height as is necessary for the ordinary use and enjoyment of his land and the structures upon it; and declaring that above that height he has no greater rights in the air space than any other member of the public."

Allen v Greenwood [1979]Court of Appeal: This case illustrate the important decision in respect of the easement of light. It makes clear that the amount of light which can be acquired as an easement is to be measured according to the nature of the building in question and the purpose for which it is normally used.

Colls v Home & Colonial Stores Ltd [1904] House of Lords: The amount of light which can be acquired as an easement is such amount as was required according to the ordinary notions of mankind for the beneficial use of premises.

Carr-Saunders v Dick McNeil Associates Ltd [1986] QB: In the case of business premises the right to light is sufficient light for the use of the premises for its ordinary uses. The case states that the question is not how much light has been taken but how much is left. The extent of the dominant owner's right is neither increased nor diminished by the actual use to which the dominant owner has chosen to put his premise or any rooms in them; for he is entitled to such access of light as will leave the premise adequately lit for all ordinary purposes for which they may reasonably be expected to be used. It will include all other potential uses to which the dominant owner may reasonably be expected to put the premises in the future.

Re Ellenborough Park, Powell v Maddison [1955] Court of Appeal: This is the leading authority on the essential characteristics which a right must possess in order to be capable of being an easement. First, easement cannot exist 'in gloss' (i.e. appurtenant to any land). Second, as to the need for an easement to accommodate the dominant tenement, this requirement would not be satisfied if the right is for the personal advantage of someone. Third, the requirement that the dominant and servient owners must be different persons arises from the fact that a person cannot have a right over his own land (i.e against himself). This requirement is satisfied if the two tenements are owned by the same person but are occupied by different person, Fourth, the right must be capable of forming the subject matter of a grant, i.e. the right must be sufficiently definite and that there must be both a capable grantor and grantee. The right must also be a kind already recognised as capable of being an easement.

Batchelor v Marlow (2001) Court of Appeal: the decision by the court demonstrates that a crucial factor in seeking to establish an easement is that the right claimed must leave the servient owner with reasonable use of the land.

Copeland v Green half [1952] Ch: This case laid down the principle that for a right to be an easement it must be a right against other land and not a right to possession of the other (i.e. servient) land.

Nickerson v Barraclough [1981] Court of Appeal: This case is about a landlocked except for an access to a highway over a bridge onto a lane belonging to the defendant who denied any right of way. The court of first instance held that an easement of necessity will exist if the land are made unusable and that there is a rule of public policy that no transaction should without good reason, be treated as effectual to deprive land of any means of access. However, the Appeal Court held that the doctrine by way of necessity was based on implication from circumstances and not public policy. Where an alternative route - albeit inconvenient - is available there can be no easement of necessity (Titchmarsh v Royston Water Co Ltd (1899).

Wheeldon v Burrows (1879) Court of Appeal: This is the leading authority on the acquisition of easements. The rule in Wheeldon is one of the ways in which an easement can be acquired by implied grant. The case laid down that on the grant of part of a tenement there would pass to the grantee as easements all quasi easements which were continuous and apparent; or necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the land granted; and used by the grantor at the time of the grant for the benefit of the part granted.

Now, you are at risk that soon, you will be asked to move out of your house due to the high risk of collapse. Nobody wants to buy your house and you have hundreds of thousands in mortgage loan to settle with your bankers.

Read this story:

House owners in Villa Aseana, a new housing project in Mount Kiara are angry that a 10m high wall has been built behind their new houses.

The developer of the land next door, Merge Power S/B erected the wall so that it could fill up the land’s sloping terrain with earth for its building project.

The wall however has showed signs of cracks and soils from the other side are leaking through the cracks. The residents had written to city hall and City Hall had issued an order to the developer to tear down the wall. The approved plan only allowed a 1m high wall. City Hall said they had given the developer one month’s notice to take down the wall or sent in the amended drawings for approval. City Hall said they will continue to monitor the developer and ensure that they abide by the plan.

What will you do if you are the dominant owner? What is your rights against the servient owner?

Let's look at a few English cases:

Bernstein v Skyviews & General Ltd [1978] QB: The case establishs that a landowner does not have unqualified rights over the airspace over his land. Facts: Skyviews employee flew over Bernstein's land, took photograph of his house and offered it for sale to Bernstein. Bernstein too exception and sued for trespass. Griffith J. dicta: "I can find no support in authority for the view that a landowner's rights in the air space above his property extend to an unlimited height. The problem is to balance the rights of an owner to enjoy the use of his land against the rights of the general public to take advantage of all that science now offers in the use of air space. This balance in my judgment is to restrict the rights to such height as is necessary for the ordinary use and enjoyment of his land and the structures upon it; and declaring that above that height he has no greater rights in the air space than any other member of the public."

Allen v Greenwood [1979]Court of Appeal: This case illustrate the important decision in respect of the easement of light. It makes clear that the amount of light which can be acquired as an easement is to be measured according to the nature of the building in question and the purpose for which it is normally used.

Colls v Home & Colonial Stores Ltd [1904] House of Lords: The amount of light which can be acquired as an easement is such amount as was required according to the ordinary notions of mankind for the beneficial use of premises.

Carr-Saunders v Dick McNeil Associates Ltd [1986] QB: In the case of business premises the right to light is sufficient light for the use of the premises for its ordinary uses. The case states that the question is not how much light has been taken but how much is left. The extent of the dominant owner's right is neither increased nor diminished by the actual use to which the dominant owner has chosen to put his premise or any rooms in them; for he is entitled to such access of light as will leave the premise adequately lit for all ordinary purposes for which they may reasonably be expected to be used. It will include all other potential uses to which the dominant owner may reasonably be expected to put the premises in the future.

Re Ellenborough Park, Powell v Maddison [1955] Court of Appeal: This is the leading authority on the essential characteristics which a right must possess in order to be capable of being an easement. First, easement cannot exist 'in gloss' (i.e. appurtenant to any land). Second, as to the need for an easement to accommodate the dominant tenement, this requirement would not be satisfied if the right is for the personal advantage of someone. Third, the requirement that the dominant and servient owners must be different persons arises from the fact that a person cannot have a right over his own land (i.e against himself). This requirement is satisfied if the two tenements are owned by the same person but are occupied by different person, Fourth, the right must be capable of forming the subject matter of a grant, i.e. the right must be sufficiently definite and that there must be both a capable grantor and grantee. The right must also be a kind already recognised as capable of being an easement.

Batchelor v Marlow (2001) Court of Appeal: the decision by the court demonstrates that a crucial factor in seeking to establish an easement is that the right claimed must leave the servient owner with reasonable use of the land.

Copeland v Green half [1952] Ch: This case laid down the principle that for a right to be an easement it must be a right against other land and not a right to possession of the other (i.e. servient) land.

Nickerson v Barraclough [1981] Court of Appeal: This case is about a landlocked except for an access to a highway over a bridge onto a lane belonging to the defendant who denied any right of way. The court of first instance held that an easement of necessity will exist if the land are made unusable and that there is a rule of public policy that no transaction should without good reason, be treated as effectual to deprive land of any means of access. However, the Appeal Court held that the doctrine by way of necessity was based on implication from circumstances and not public policy. Where an alternative route - albeit inconvenient - is available there can be no easement of necessity (Titchmarsh v Royston Water Co Ltd (1899).

Wheeldon v Burrows (1879) Court of Appeal: This is the leading authority on the acquisition of easements. The rule in Wheeldon is one of the ways in which an easement can be acquired by implied grant. The case laid down that on the grant of part of a tenement there would pass to the grantee as easements all quasi easements which were continuous and apparent; or necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the land granted; and used by the grantor at the time of the grant for the benefit of the part granted.

In essence, the rights capable of being easements are:

#A right to receive light through defined aperture in a building;

#A right to the passage of air through a defined channel;

#A right to have a building supported by the wall of another building;

#A right to require the servient owner to fence his land;

#A right to park a vehicle in a defined area but must not leave the servient owner without any reasonable use of his land;

#A right to the passage of piped water across another person's land;

#A right to a view:

#A right to privacy;

#A right to general flow of air over land.

The fundamental rule of law is that user of the rights must not use force in order to enjoy the claimed right, nor must user take place under protest from the servient owner (Nec vi). User who enjoyed by permission cannot be as of right (Nec precario).

1 comment:

Good Work Law Essay

Post a Comment